When

Bob Paris and Rod Jackson “wed” in a 1989 commitment ceremony,

their marriage seemed to energize gay men and lesbians, especially

those already involved in the struggle for legal marital rights. After

all, here was a couple tailor-made for that struggle. Especially among

gay males—a community that often worships the body beautiful—Paris

and Jackson were not just men. They were gods. And their love was

forever. With their chiseled good looks and public devotion to each

other, the two became instant poster boys for gay marriage.

When

Bob Paris and Rod Jackson “wed” in a 1989 commitment ceremony,

their marriage seemed to energize gay men and lesbians, especially

those already involved in the struggle for legal marital rights. After

all, here was a couple tailor-made for that struggle. Especially among

gay males—a community that often worships the body beautiful—Paris

and Jackson were not just men. They were gods. And their love was

forever. With their chiseled good looks and public devotion to each

other, the two became instant poster boys for gay marriage.

The meteoric rise to fame that Jackson

and Paris experienced also underscored a sad truth for lesbians and

gays: the lack of images that illustrate valid long-term gay relationships.

For many people, both gay and straight, enduring images of gay love

were long ago supplanted by more-facile images of gay sex: the backroom

encounter with an always-anonymous sexual partner. And even though

there are thousands of gay and lesbian couples in successful long-term

relationships, when listing famous out gay couples—those attractive

and instantly recognizable faces that might best illustrate to the

world the concept of long-term love—one comes up shorthanded.

Jackson and Paris seemed to fill that gap. Or at least gays and lesbians

tried to fill the gap with them.

That is, until bad times set in and

did to the Jackson-Paris marriage what domestic difficulties often

do to any other marriage, gay or straight. After months of speculation

about the state of their union, Jackson and Paris finally confirmed

the rumors in a July 18 press release. “The details and reasons

for our separation are complicated, painful, and personal, as they

are when any marriage fails,” read the couple’s prepared

statement. “And while our marriage was lived in the public eye

for many years, its demise is not a subject either of us can expand

upon in the media.”

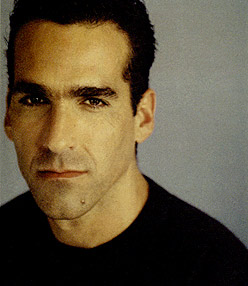

Now, several months after that disclosure,

Paris sits by the outdoor swimming pool of a Los Angeles hotel, having

agreed to discuss with The Advocate his life after his marriage

to Jackson. Dressed casually in faded jeans and a forest-green long-sleeve

shirt draped openly over a white muscle T, Paris appears less bulky

than one might imagine. Tan, his hair graying around the temples,

he is also strikingly handsome. But the lines around his eyes indicate

a wiser—and perhaps more cautious—man than the one who

entered into a gay public life less than a decade ago.

Paris, 36, is a resident of Washington

State, and he is in Los Angeles to finish up work on several new projects.

Among them is his latest book, Gorilla Suit: My Adventures in

Bodybuilding, to be published next year by St. Martin’s

Press. A former Mr. Universe and Mr. America, Paris first rose to

fame in gay circles when he came out in the bodybuilding magazine

Ironman in 1989.

Although he isn’t yet comfortable

discussing the dissolution of his seven-year marriage to Jackson,

on some level Paris knows he has to. “It was just time to set

aside the belief that it was nobody’s business,” he says,

acknowledging the role he continues to play as a public figure in

the gay community. “Honestly, I didn’t want to believe

that the breakup was true myself. I wanted to believe that the outcome

could still be changed. I mean, I pictured myself spending the rest

of my life with this person.”

During the seven years in which Jackson

and Paris were a married couple—they even legally changed their

surnames to Jackson-Paris, a symbolic act that many lesbian and gay

couples have adopted in the absence of legal marital rights—they

quickly established themselves as two of the most visible icons in

the struggle for gay and lesbian rights. And despite their bodybuilding

fame (Jackson was a featured model in Playgirl), they were

determined to be remembered for their activism.

The two began to travel extensively,

lecturing on a variety of topics that ranged from fitness and nutrition

to motivation and building self-esteem—especially among gay

and lesbian youth. They even helped establish a fund-raising organization,

the Be True to Yourself Foundation, specifically designed to aid gay

and lesbian youth throughout the country.

Strong, handsome and committed, the

two seemed to satisfy the growing hunger for an attractive image of

gay love in the age of AIDS. For a public that was increasingly bombarded

with images of the gaunt and frail, Jackson and Paris were a godsend.

Of course, they got a lot of help too. Their status as the ideal male

couple was one that was reinforced by some of the world’s top

image makers—from Herb Ritts to David LaChapelle—who photographed

the couple for everything from commercial advertisements to coffee-table

books.

Adding to their fame, the couple released

their 1994 joint autobiography, Straight From the Heart,

in which they chronicled not only their individual coming-out stories

but also the day-to-day minutiae of building a long-term gay relationship.

Unfortunately, unbeknownst to their fans, Jackson and Paris were already

beginning to experience a series of domestic problems that would inevitably

lead to their separation. For the most part Paris is unwilling to

discuss any of this, saying only that questions of “balance”—between

their public and private lives—damaged their relationship. As

the couple’s career obligations increased, Paris says, “there

became almost an inability to say no” to those demands. He also

notes that the couple’s workload of “a million hours a

week” affected their life in all the wrong ways. Worst of all,

he adds, was their increasing lack of communication. “It’s

the essential thing about a relationship,” he says. “Without

it some perspective begins to be lost, and before you know it, it

becomes too late.”

One fact is clear: Even if Paris and

Jackson hadn’t been so famous as a couple, it would have been

just as difficult for them to weather their marriage troubles, simply

because lesbians and gays have so few traditions to fall back on for

problem solving. Lesbian psychotherapist Betty Berzon, author of The

Intimacy Dance: A Guide to Long-Term Success in Gay and Lesbian Relationships,

published this year, believes there’s already too much “outside

encouragement” in breaking up gay and lesbian couples.

“We have a tradition of failure,”

she says. “There is an assumption of impermanence that we all

reinforce, and it becomes almost a habit. People come into my office

and say either, ‘Gay relationships don’t work’ or

‘They’re good for about three years.’ Those are

two myths that are destructive in terms of our building the kind of

durable relationship tradition we need.”

Berzon adds that this “tradition

of failure” is further perpetuated by a lack of role models.

“How are you supposed to have an idea of what a long-term, successful

relationship is if you don’t know anybody who’s been in

one?” she asks. “Especially when the surrounding society

is telling you that these relationships don’t count, can’t

last, and won’t work. With enough negativity many gay people

simply internalize that and believe it themselves and act accordingly.”

Paris agrees. “A lot of the cynicism

about relationships in our community comes from being told all our

lives that we're worthless, that we’ll always be less than straight

people, and that we’ll never be happy,” he says. “We

need some lessons on how to make things work, and the way that happens

is by having people who have successful relationships tell other people

how to make their relationships successful.”

In the case of the Jackson-Paris marriage,

Berzon believes the couple’s rise to fame was dubious. “They

certainly tuned people in to the issue of committed relationships

and commitment ceremonies,” she says. “But let’s

face it: If they were two very ordinary-looking guys who were not

very attractive, I’m not sure they would have become role models

for anything.”

Unfortunately, the dissolution of the

Jackson-Paris union may serve only to reinforce Berzon’s “tradition

of failure” theory for those gays and lesbians who looked up

to the couple as representing everlasting love. Author Eric Marcus,

who co-wrote Straight From the Heart with the former couple,

argues that it’s unfair of lesbians and gays to blame their

disillusionment on Jackson and Paris. “It’s tough to talk

about relationships publicly without people seeing that as an effort

to hold yourself up as a role model,” says Marcus. “But

we have unfair expectations of people who are in the public eye, and

we’re bound to be disappointed.”

Not that Marcus wasn’t disappointed

too. “I was stunned when I heard that they had broken up,”

he says. “In part because they had separated so long before

the news was made public. But the bottom line is, these guys are still

human, and the possibility always exists that things will not go as

you expected.”

That’s why both Marcus and Berzon

believe gays and lesbians might be wiser to seek out role models in

their everyday lives rather than in the public arena. Of course, to

do that, Marcus and Berzon acknowledge, takes some effort.

For instance, says Berzon, “one

of the biggest problems in our community is that we don’t socialize

intergenerationally. Young people stay with young people, and older

stay with the older. The young people don’t get to experience

couples who’ve been together for 15, 20, 25, 30 years. And frankly,

I don’t see that changing.”

Whether Jackson and Paris actively

courted the devotion of gays and lesbians or it was forced on them,

their fame as a couple made it more difficult for them to split up.

As a professional bodybuilder, Paris had already entered the public

eye before he ever met Jackson. But it was their partnership that

made them both celebrities. By the time their marriage began to crack,

their livelihoods were intricately tied to their fame as a couple.

It was an agonizing situation, and at first they tried to hide it.

They continued to make joint appearances even though they had privately

separated. In a classic understatement, Paris describes this time

of life as “extremely difficult.”

Once they did go public with their

separation, there were more difficulties. At the center of those troubles

was the Be True to Yourself Foundation, which was completely dependent

on the couple for its fund-raising efforts. Predictably, word of a

Jackson-Paris split sent it into a tailspin. “There was some

level of shake-up,” Paris admits, “[but] we had already

been working with the board of directors to move the foundation away

from revolving around our image even before it became apparent that

the breakup was going to happen.” Can the foundation survive

the couple’s dissolution? Says Paris, “I’m not sure.”

Along with these financial concerns

came the issue of division of property between the two men. Paris

will not comment on those particular negotiations—and in that,

he’s like many gays and lesbians, who, when ending a relationship,

usually do it behind closed doors with few rules to help them along.

Roberta Bennett, a Los Angeles-based

attorney and out lesbian who has practiced family law for 20 years,

says it is infinitely more difficult for gays and lesbians to separate

property than it is for heterosexual couples, simply because gay men

and women cannot legally marry. “Once heterosexual couples marry,

the division of their property is governed by the community-property

laws in whatever state they live,” she says. “Because

we cannot legally marry, we don’t have that structure.”

Given the situation, says Bennett,

there are three ways in which gay and lesbian couples who are separating

can divide their property: The first is a written contract, also known

as a cohabitation agreement, which outlines a couple’s financial

agreement before a relationship terminates. The second is an oral

contract. The third is a process that allows the courts to intervene

in case there are no contracts. Bennett suggests that, given these

options, couples should sign a written contract when they first move

in together, “It’s the safest way to approach the termination

of a relationship,” she says.

With the fallout of his own breakup

still lingering in his thoughts, Paris is unsure what the future holds.

He wants to continue to play a part in the struggle for gay rights—and

gay marriage—but he doesn’t know what that role might

be. He admits that he and Jackson have not spoken for several months.

He also confides that he’s entered into his first steady relationship

since the breakup. He even continues to extol the joys of monogamy.

“I’m a one-man man,”

he says. “That’s how I function. And it’s absolutely

no judgement whatsoever on people who structure their lives differently

from that. All I ask is that if you do believe in structuring your

life in a monogamous way, that your desire not be condemned as impossible.”

Perhaps most surprising is Paris’s

unwillingness to discount the possibility of future wedding bells

in his own life. “I’ve rediscovered a part of my heart,”

he says. “I think I make a very good partner and a very good

spouse. If you had asked me six months ago, I probably would have

said no. But at this point in my life, I can say yes—I would

commit again.” Then, as a befits an older and wiser man, he

adds a note of caution: “Given the right circumstances.”

*article

from The Advocate, December 10, 1996